1619: American History, Critical Race Theory or Both

- Editor Ellis

- Dec 1, 2022

- 3 min read

Four hundred plus years ago “twenty some odd” African embarked on the shores of the British colony of Virginia and were sold to colonizers by pirates who had stolen the Africans from a slave ship. This lone transaction set in motion a racial maelstrom that is at the bedrock of what became the United States.

Three years ago, New York Times staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones used her Black Girl magic and convinced her newspaper to commemorate slavery’s 400-year anniversary by publishing a compilation of essays detailing the impact of slavery on what was then a burgeoning nation.

Like those “twenty some odd” Africans in the hull of that 1619 slave ship, Hannah-Jones’ life hasn’t been the same since.

The Pulitzer Prize winning author and now professor at HBCU Howard University recently regaled Cleveland area audiences in a Zoom event sponsored by the Cleveland Public Library.

Hannah-Jones spoke to Clevelanders through the library’s Writers and Readers Series, which was moderated by Black Girl magician in her own right, Connie Hill-Johnson, chairperson of the vaunted Cleveland Foundation – the first African American woman to hold that post.

“Man, was she easy to talk to,” said Hill-Johnson, who was recruited to serve as moderator by library officials. “She lit up when she started talking about her daughter and teaching kids about their history.”

Hannah-Jones, an Iowa native, has established a school in her home state that focuses on a 1619 Project curriculum, and she is presently working with the Disney Corporation on a 1619 documentary scheduled to air next January.

“The Project,” as the work came to be known during its inception, asserts that fateful day in 1619 when slaves were first traded on these shores, has had more influence on American history than the Revolutionary War itself.

Through a series of essays written by Hannah-Jones and others, the project asserts that slavery in the United States has impacted partisan politics, the economy, the arts, and medical science just to name a few.

Take, for example, partisan politics. Long before the Republican Tea Party grew up out of a backlash against the nation’s first Black president in Barak Obama, southern Democrats during Reconstruction were concocting political strategies to continue national oppression of newly-freed African Americans.

Even today’s racial wealth gap had its origins in the vestiges of slavery.

After the Civil War when U.S. General William Sherman began allocating 40-acre plots of land to emancipated African Americans, the order was soon rescinded by President Andrew Johnson, who took office after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

“This is a country for white men,” Johnson said in 1866., “and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men.”

The project contends that views like these permeate the American landscape and have far-reaching implications in American life. The project posits slavery and general attitudes of anti-Blackness at the core of racial disparities in healthcare, property rights, even American music has been appropriated from Blacks by many white artists.

It’s ideas like these that aroused the ire of critics of the 1619 project in academia and even the halls of the U.S. Congress. Opponents of the project asserted that it took a dim view of American history, and their opposition began casting the work as an example of critical race theory, a bogeyman created by those who resisted this candid look at America’s greatest sin.

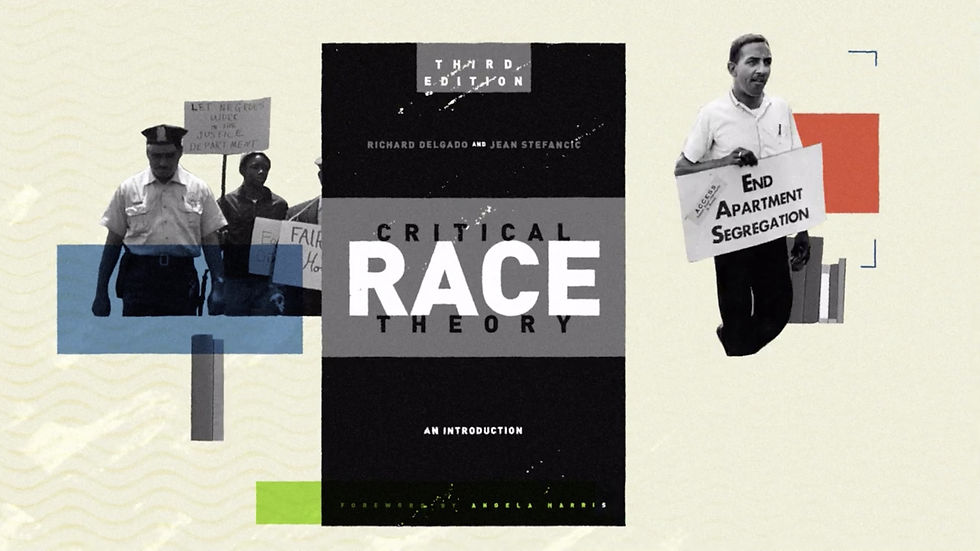

Critical race theory is a legal construct which asserts that racism because of its prolonged and largely unchecked practice in the U.S. has been “baked into” institutions like the criminal justice system, the media, law, and politics.

“(W)hite Americans desire to be free of a past they do not want to remember, while Black Americans remain bound to a past they can never forget,” Hannah-Jones wrote in the foreword of the book on the 1619 project.

Hannah-Jones hopes the upcoming documentary will have the same effect on American audiences – Black and white -- as the 1977 television miniseries Roots had on audiences back then. Alex Haley’s saga of African American life brought dignity to the plight of enslaved Africans on these shores and was one of the most-watched television shows in history.

The 1619 Project, like Haley’s Roots, has clearly struck and American nerve. That alone is reason enough to read and study it.

Comments